So, my biggest problem with RPGs is that I don’t have time to play them. In the last few years I’ve started but not finished The Witcher 3, Fallout 4, Dark Souls, Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, and numerous others. As I wrote about two months ago, I also started Mass Effect: Andromeda and have since finished that (I think I just get more immersed in space opera than fantasy RPGs). And I’m not someone to abandon a game lightly. I even now keep a spreadsheet of games bought vs started, finished, and abandoned or dropped in favour of watching a YouTuber finish it. There’s just been an increase in releases, sales, and bundles, and a decrease in the free time I have that’s taking a toll on my game completion, especially in RPGs.

This problem, though, is exacerbated by my second biggest problem with (most) RPGs – inventory management. Actually, this would apply almost equally to most survival/crafting games, but I’ll focus on RPGs today.

RPG stands for role-playing-game (or rocket-propelled-grenade. Just for the sake of pedantry). You’re supposed to get very involved with your character, whether they’re an original creation of your own, or a given hero like Geralt of Rivea. You’re meant to come to see the world through their eyes and get totally immersed in the experience of deciding what that character would do in hundreds of given situations.

Designers go to great lengths to make actions and dialogue choices affect the world around you minutes, hours, and even years later in the case of the original Mass Effect trilogy, where some minor choices could resonate into the sequels. Huge budgets often go into making the worlds vast and sprawling, with dynamic weather, super-realistic lighting and shadows, and natural NPC and animal AI. This is all to make us feel more invested in the world; like it’s a living, breathing place that we’re really escaping to for a few hours.

The problem is that (and I’ll take The Witcher 3 as a recent personal example), every time I do get a few hours to come back to my save file, I take a look at my inventory and between the dozens of clothing items, clubs, swords, foods, potions, and wolf guts that I’m apparently fitting inside my pockets, I can’t remember if I’m wearing optimal armour, or checked to see if I’m using the best weapon, and the first thing I get, before any gameplay enjoyment, is the frustration of choice paralysis. I’m certainly not immersed, yet.

Then I think to myself, if I’m role playing a demon hunter riding around the countryside on horseback, why am I even carrying this much stuff? I should be travelling light, with only vital supplies and potions. You could argue that it’s my fault for picking stuff up, but that’s a pretty central tenet of all RPGs, which is actually my main problem with the genre (me not having enough time isn’t really the genre’s fault). In fiction, Geralt even repeatedly mentions that he carries two swords. A silver one for monsters, and a steel one for humans or animals. Why, then, would he pick up and carry a dozen clubs and maces (that he can’t even wield in the game), ten other steel swords, and whatever else he’s got?

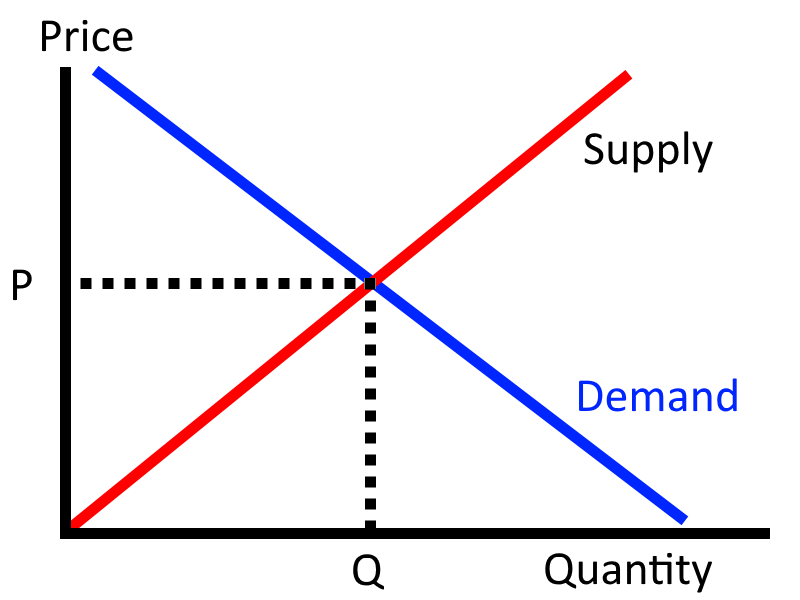

Don’t say ‘Economy’

It’s an RPG trope to just hoard everything until you can get to a shop to sell it, so you can buy new things. In most games there’s an ‘overburdened’ mechanic that slows you down or otherwise impedes your abilities if you carry too much, but that’s a weak ‘fix’ to the issue of being incentivised to carry around half of the world’s economic resources in your backpack.

Just because it’s a trope doesn’t mean that it’s good design, or even that players would miss it if it was gone. Yes, if you gave less ‘loot’ for kills and treasure chest raids, then shop items would be harder to afford. There’s a very simple fix to that. You either lower the game’s prices for items, or give more gold for quests and less for selling loot. Solved. That’s part of the game balance process during production anyway. Players will never see it.

Immersion

I see The Witcher 3 praised (and rightly so) all the time for its story, gameplay, animations, etc, but nobody that I’ve seen has ever talked about why Geralt would/could carry so much stuff around and raised that as a negative. Each time I came back to the game this got in my way and ruined my immersion a bit. In a game that has magic as a world element, you could argue that the items are shrunk, and that’s okay, but I don’t think they do it here (correct me if I’m wrong). And either way it’s not fun. In a sci-fi game you could say that nano machines instantly form the item you want when you want it, and return to a dormant state when you’re finished so you’re carrying around less mass but have access to several blueprint items that form and reform on command. But still, inventory management is just not fun when compared with the main game’s activities. Why must it take so much time?

Magic bags and nano machines are ‘okay’ answers by themselves, but I do think that they need to be addressed by the story in order to be acceptable, and I still think it’s preferable to make the player make interesting decisions about what to carry.

I would like to see you carrying less items in most RPGs. Elements of RPG design (specifically experience curves and customisation options) have snuck into most other game genres in the last decade, especially first person shooters, but not as many action elements have come into real time RPGs.

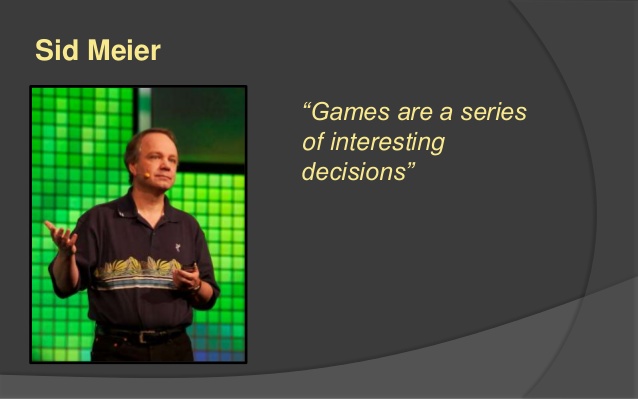

For example, a lot of shooters like Spec Ops: The Line or Gears of War will only let you carry two main weapons (and maybe a pistol as a third), plus grenades. Ideally you’d want something for close, medium, and long ranges, and probably something for heavy targets like an RPG (grenade, this time) launcher. This makes it impossible for you to hoard items and instead has you make interesting decisions about what you think is coming and what your play style is.

In Fallout 4 I wound up carrying so many different weapons that I thought I was playing a 90s FPS, and I often got overburdened.

Steal everything!

Another symptom of this problem is that because the game is balanced (presumably) to have good items available in shops for lots of money, you’re encouraged to loot everything from everywhere just in case that last cooking pot represents the last few credits you’ll need to afford the gold plated armour in the next town.

I actually hate this about RPGs. It’s fine to role play a villain or nefarious character, if that’s your thing, but I usually go paragon/good, and it’s totally at odds with the character I’m role playing to do a side quest to save this poor, starving person from the gang who’s threatening to rob her apartment, just to turn around, break into her home, and take everything myself, as she thanks me walking out the door. I didn’t even want her vase, I just took it because I could.

Someone will now tell me I’m playing it wrong. Well, I’m not, really. What’s the right way? That’s the point of RPGs, isn’t it? But it does feel wrong to me. Gamers become experts at min-maxing game systems. It just becomes second nature to find the most efficient ways to do something, and stealing to get free resources is just good gaming (because an NPC isn’t going to care or be affected the vast majority of the time), but it completely ruins the game’s immersion while you’re doing it, and when designers are trying to have people reach flow states, that’s a cardinal sin! It needs to be designed against.

As a side note, Fallout 4 is actually the first game I’ve ever played where I was more immersed as a result of not looting everything that I could. I started out that way, but found quickly that there were actually too many locations (and shopkeepers had limited funds) for me to bother hoarding items just for currency. So, kudos there. And that’s not even in survival mode, where your inventory is vastly more limited. In Deus Ex games, the levels are far more linear and so you can quite easily do every side quest, help every NPC, then rob every item. The interesting choice about what to buy in a store is usually lost because the decisions becomes not “item-A, or item-B”, but “let’s steal items C-Z then come back to sell them and buy both A and B”. It basically generates busy work (to go steal C-Z) and artificially lengthens the game. That could almost be seen as a plus if you can stay immersed while doing it, but I can’t.

In Mass Effect: Andromeda I didn’t even look at what I was picking up any more after a few hours. I rarely went to shops and when I did I’d buy the most expensive stuff, sell all my ‘junk’ in a single button press, throw in a few extra shotguns and rifles I had lying around, and walk out with more credits than I went in with, plus the new vehicle upgrades. I like a lot about that game, but I had utter contempt for the inventory and the god-awful layout of the research and crafting trees. I just found weapons and armour early on that I liked and pretty much used them for the rest of the game, without ever feeling like the enemy were too powerful for my current gear level. How many hours of work went into just a couple of mechanics that only got in my way and made me feel contempt for that part of the game? Not worth it! Simplify! Cut the fat!

Define the problem

I think I’ve been pretty clear so far, but when trying to solve a problem, it’s good to be very clear about its definition. So allow me to suggest:

“The glaring weak point in the RPG genre is its looting and inventory systems, which slow the game’s pace and break immersion”.

For me, that statement is complete enough. As an example, I find that in many RPGs I spend about half my time (or at least far too much of it) considering what to loot, reading item descriptions, going back and forth between different gun stat listing to weigh the pros and cons of changing my primary weapon, and generally not playing the game!

Talk about solutions

This is just me talking, but I know from pervious chats that others agree with me. There are dozens of us! Dozens! I’ll confess that I’m not traditionally an RPG guy. I didn’t get into Baldur’s Gate back when it was big, I haven’t played Dragon Age, Pillars of Eternity, or any Bethesda game before Skyrim, and I don’t think I’ve ever played a table-top RPG yet (though I really want to). So I’m an RPG-pleb coming from the shooter world into this great genre, which really first captivated me when it went sci-fi and first/third person. So maybe there are purists who love the systems exactly the way that they are, but I think there are improvements to be made.

I’m not about to tackle making an RPG myself, but I’d encourage any designers reading this to approach their next RPG from the ground up. Take out looting completely and see if the game is fun. Then add back in interesting decisions around looting, weapon management, and the economy, with a very deliberate focus on “what would our lead character do in this world?” instead of “it’s an RPG so you have to be able to loot lots of stuff”. Have looting and weapon management for good, synergistic reasons, not just because it’s a genre norm.

In Conclusion

I think I already concluded, really. But I don’t hear others talking about this much, especially not in relation to The Witcher 3. I’d love to hear your thoughts, and whether you’re a classic RPG player, or a recent blow-in.

Until next time…